In recent years, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) has made significant changes to top-level domains (TLDs) and internet addressing. These changes have implications for security, as they present opportunities for threat actors to exploit vulnerabilities and engage in malicious activities such as phishing and malware distribution. In this article, we will explore two important developments:the inclusion of non-Latin characters, including Cyrillic, Arabic, and Chinese, in generic top level domains (gTLDs) and the introduction of new gTLDs like .zip and .mov. By examining these issues, we can better understand the potential security risks and explore strategies to mitigate them.

TLD is one of the highest levels in the internet’s hierarchical Domain Name System (DNS), after the root domain. TLD names are installed in the root zone of the name space. For all domains in lower levels, it is the last part of the domain name, that is, the last non-empty label of a “fully qualified domain” name. The term “generic” is used to distinguish it from the two-digit country codes: gTLD.

For example, in the domain name www.exabeam.com, the TLD is .com. Other common commerce and organizational domains include .gov, .mil, .net, .org, .biz, .info. Some, like .pro are designated as “restricted” because registrations within them require proof of eligibility within the guidelines set for each.

Around 2019, problems emerged with the way web browsers recognized gTLDs and resolved strings. (This one was a favorite of mine, where browsers didn’t quite recognize the desire to resolve new URLs.) And with the introduction of gTLDs — which are also the same as the acronyms for formats in which electronic data is stored and shared with web sites, namely .mov and .zip — as they say, “Houston, we have a problem.”

In this article:

- Potential security issues with new gTLDs

- Best practices for the new gTLDs

- How Unicode and non-Latin characters can deceive users

- Conclusion

- Next steps

Potential security issues with new gTLDs

The recent addition of .zip and .mov as new gTLDs raises security concerns. These domains can be exploited by adversaries for phishing attacks and the distribution of malware. For example, a user may be tricked into believing they’re downloading a legitimate .zip file when, in reality, they are being redirected to a location hosting malware.

To exacerbate the issue, there already exists a list of known malicious .zip domains. Additionally, most web browsers currently lack the capability to adequately detect and handle these gTLDs. As a result, these browsers initiate the download process without scrutiny when provided with a URL for such files. An example of this can be seen on the Github for Kubernetes:

https://github.com/kubernetes/kubernetes/archive/refs/tags/v1.27.1.zip

I promise, as of this writing, this link is official and harmless. But this is what you look for, right? .zip is a file! If you want to dig deeper, this is a good Medium article on the topic.

Best practices for the new gTLDs

To protect against potential threats, I recommend proactively blocking .zip and .mov domains, as well as any future gTLDs that correspond to standard file extensions. Blocking these domains at firewalls and endpoints, and treating *.zip and *.mov as inherently hostile to your work environment can help prevent security incidents.

How Unicode and non-Latin characters can deceive users

ICANN’s decision to allow non-Latin characters in URLs is a laudable advancement in making the internet accessible to users worldwide. This inclusive approach allows individuals from diverse linguistic backgrounds, including Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Cyrillic, and other MBCS-speaking communities (or DBCS, depending on your perspective on the nomenclature debate), to surf the web in their native language. It ensures that the internet becomes a platform where people can interact and access information comfortably in languages they understand.

However, this change also creates opportunities for adversaries to deceive users through social engineering attacks. By leveraging Unicode and non-Latin characters, adversaries can manipulate URLs to appear legitimate while harboring malicious intent. For instance, an altered version of the previously mentioned Github .zip URL might fool even the most seasoned security veteran. Consider this more malicious version of the URL:

https://github.com∕kubernetes∕kubernetes∕archive∕refs∕tags∕@v1271.zip

In this modified URL, what appears to be a regular forward slash between “kubernetes” and “kubernetes” is, in fact, a fractal slash — a character from the Unicode mathematical set. Additionally, the presence of the @ sign in the URL should further raise suspicion. Adversaries cleverly utilize combinations of Unicode characters and symbols to create URLs that closely resemble legitimate ones, making it challenging to discern their nefarious motives.

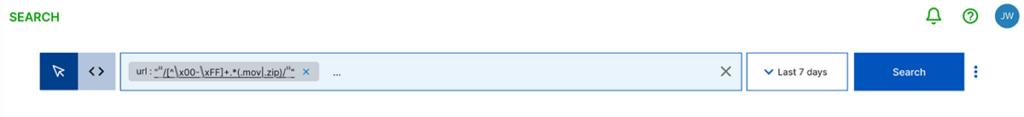

Joe Thompson, one of our amazing security architects, helped devise a good search query string to find both the unicode character or any .mov or .zip URLs:

url: "/[^\x00-\xFF]+.*(.mov|.zip)/"

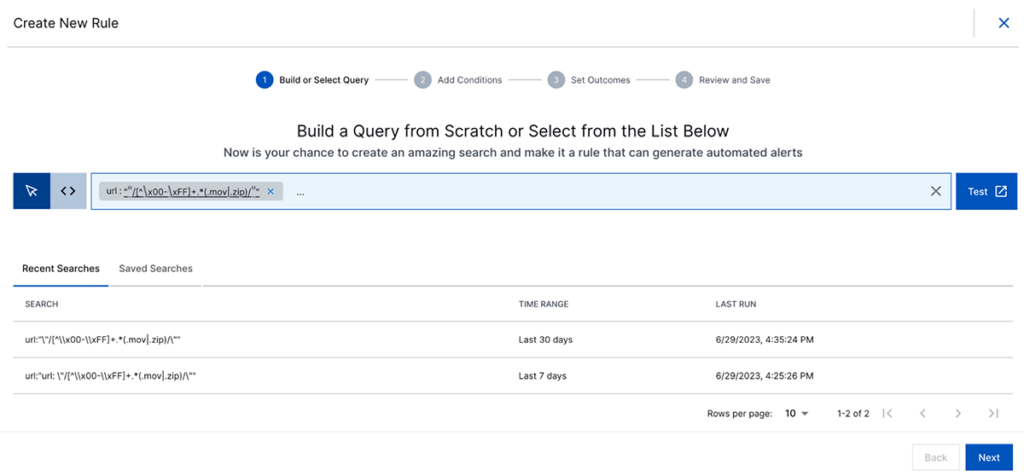

In Exabeam Search, it looks like this:

My advice would be to modify this to encompass other Unicode characters that may be captured, such as the character “ ‘ “. Here’s an example of how you can adapt it:

url: "/[^\x00-\xFF’]+/"

But these individual characters are just the starting point. If you’re looking for a comprehensive article that explores the differences between “allowed” URL characters and their Unicode alternatives, along with the regex expressions that support your searches, I found a valuable resource on Stack Overflow. It gave me information to experiment with on our Exabeam Fusion and Exabeam SIEM demo sites.

Additionally, creating a “not allowed list” of domains within a correlation rule or dashboard would be beneficial. As a security analyst, you are aware that it’s not always feasible to block an entire domain due to business partnerships or other factors beyond your control. In such cases, setting up a rule to fire and notify your network team to investigate any suspicious activity, providing them with the necessary information to take appropriate actions is advisable.

I would recommend creating this under rule conditions as a block list. You can then decide whether you prefer to receive an alert, an email notification, or export the information into a secondary ITSM system via a webhook. This approach allows your network team to review the details and make an informed decision. It provides them with the opportunity to validate your recommendation and potentially realize that blocking the domain at the firewall from the outset would have been the correct thing to do.

Conclusion

As ICANN continues to introduce new gTLDs and Unicode characters gain prominence in URLs, it is imperative for organizations to remain vigilant and proactive in their security practices. By harnessing the capabilities of security information and event management (SIEM) or user and entity behavior analytics (UEBA) platforms, security teams can efficiently detect hosts and URLs that deliver malware, enabling them to promptly identify and mitigate threats originating from malicious domains and deceptive URLs.

It is important to acknowledge that adversaries will continuously strive to adapt their malicious URLs and delivery mechanisms to evade detection. Nonetheless, the ability to identify crucial elements that should not pass through firewalls, email security systems, and other security measures is vital.

Employing block lists. especially for those incorporating regex expressions for non-standard URL characters, can be highly effective in preventing security breaches. However, if restrictions prevent the implementation of these measures on perimeter systems, it is advisable to establish rules that alert you whenever traffic to or from such sites occurs. This ensures that any potential compromise of entities or credentials is promptly identified and addressed to prevent further security incidents down the line.

Next steps

If you are new to using the Search function on the Exabeam Security Operations Platform, refer to the documentation for comprehensive guidance on getting started.

And if you’re interested in building a dashboard to visualize and analyze your security data and the results of your correlation rules, here’s an excellent video that offers step-by-step instructions. By creating a customized dashboard, you can gain valuable insights into the security posture of your organization, enabling you to identify patterns, anomalies, and potential security risks more effectively.

Similar Posts

Recent Posts

Stay Informed

Subscribe today and we'll send our latest blog posts right to your inbox, so you can stay ahead of the cybercriminals and defend your organization.

See a world-class SIEM solution in action

Most reported breaches involved lost or stolen credentials. How can you keep pace?

Exabeam delivers SOC teams industry-leading analytics, patented anomaly detection, and Smart Timelines to help teams pinpoint the actions that lead to exploits.

Whether you need a SIEM replacement, a legacy SIEM modernization with XDR, Exabeam offers advanced, modular, and cloud-delivered TDIR.

Get a demo today!