The Clipper Chip: How Once Upon a Time the Government Wanted to Put a Backdoor in Your Phone

At Exabeam, we’re not only interested in developing the newest cybersecurity, we’re also fascinated by what we can learn from older security technologies. That’s why we recently created a History of Cybersecurity 2019 Calendar. Each month features key dates in cybersecurity history, along with a related trivia question and other things of interest that occurred in that month during years past.

This is fourth in a series of posts featuring the Cybersecurity Calendar where we look at the rise and fall of the Clipper chip. We’ll be publishing more history around the cybersecurity dates we’ve researched throughout the year. If you think we missed an important date (or got something wrong), please let us know. You can also share your feedback with us on Twitter.

Privacy also mattered in your parents’ era

How would you feel if you discovered your phone contained a chip specifically designed to turn over your private communications to the government? You’d probably be shocked and demand answers from the manufacturer, at a minimum. Today, people are rankled by comparatively minor eavesdropping, such as marketers using their computer browsing histories or their mobile phone’s GPS to feed them targeted advertising. Now imagine how people felt in the 1990s when the US government developed and promoted a chipset designed with a built-in backdoor.

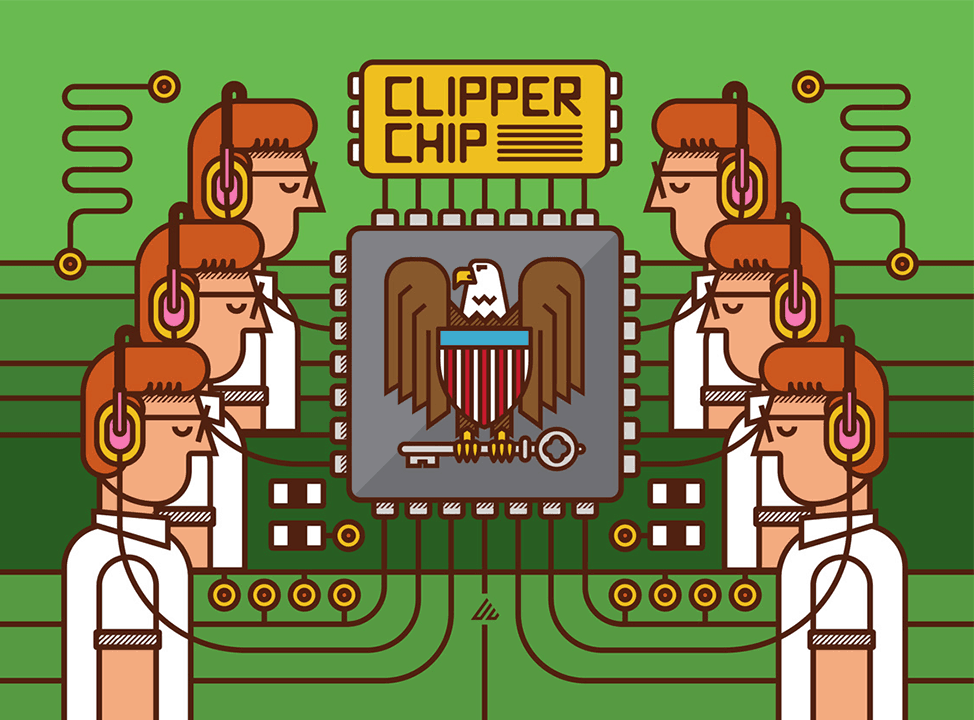

On April 16, 1993, the White House announced the so-called “Clipper chip.” Officially known as the MYK-78, it was intended for use in secure communication devices like crypto phones, which protect calls from interception by using algorithms and cryptographic keys to encrypt and decrypt the signals. The chip’s cryptographic algorithm, known as Skipjack, was developed by the National Security Agency (NSA), the deeply secret military intelligence agency responsible for intercepting foreign government communications and breaking the codes that protect such transmissions.

Each Clipper chip had a secret unit key programmed into it during manufacture. Since each chip had its own serial number and key unit, each secure communications device using the technology would be unique.

But in the case of the Clipper chip, the “secure” part didn’t really apply to the government. In a secure communication system like a crypto phone, having the right cryptographic keys enables a phone to decrypt voice signals so the receiving party can hear the call. With the Clipper chip, device manufacturers were required to surrender the cryptographic keys to the government. Obviously, the intent was to allow intelligence and law enforcement agencies such as the CIA and FBI to decrypt voice calls for surveillance purposes.

While today it doesn’t seem like something one would publicly announce, the concept did at least attempt give a slight nod to people’s rights to privacy. To provide some protection against misuse by enforcement agencies, the developers agreed the cryptographic key of each Clipper chip would be held in escrow jointly by two federal agencies. Essentially they split the Unit Key into two parts, and each half would be given to one of the agencies. Reconstructing the actual unit key required accessing the database of both agencies, and then putting the halves back together using special software.

Privacy advocates and cryptographers quickly moved to clip the chip’s wings

Not surprisingly, a backlash soon followed the announcement of the Clipper chip. Privacy rights organizations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Electronic Privacy Information Center balked at the Clipper chip proposal. These and other opponents claimed it would subject ordinary citizens to illegal government surveillance.

In a 1994 article, the New York Times went so far as to describe the backlash among Silicon Valley technologists as the first holy war of the information highway.

“The Cypherpunks consider the Clipper the lever that Big Brother is using to pry into the conversations, messages and transactions of the computer age. These high-tech Paul Reveres are trying to mobilize America against the evil portent of a ‘cyberspace police state,’ as one of their Internet jeremiads put it. Joining them in the battle is a formidable force, including almost all of the communications and computer industries, many members of Congress and political columnists of all stripes.”

On the other hand, the Clinton White House argued that the Clipper chip was an essential tool for law enforcement. When others suggested it could be a tool for terrorists, the administration said it would actually increase national security because the government could listen in on their calls.

The cryptographic community also complained the Clipper chip’s encryption could not be properly evaluated by the public as the Skipjack algorithm was classified secret. This could make secure communication equipment devices not as secure as advertised, impacting businesses and individuals who would rely on them.

In 1993, AT&T Bell produced the first and only telephone device based on the Clipper chip. A year later, Matt Blaze, a researcher at AT&T, published a major design flaw that could allow a malicious party to tamper with the software. That flaw seemed to have been the last nail in the technology’s coffin. The AT&T device was the first and only secure communication technology to use the Clipper chip; by 1996 the chip was no more.

Looking at the strong response to the Clipper chip and its rapid demise, we can learn a little from history about cybersecurity today. Cybersecurity technologies have to exist in a world for real people, and people today care a great deal about personal privacy. Whether innovations come from government or industry, they need to balance security with concerns for misuse of the technology. After all, most people are not criminals or terrorists. Also building flawed security technologies into systems that are promoted as “secure” can leave the individuals and businesses that trust these tools vulnerable to risks.

Similar Posts

Recent Posts

Stay Informed

Subscribe today and we'll send our latest blog posts right to your inbox, so you can stay ahead of the cybercriminals and defend your organization.

See a world-class SIEM solution in action

Most reported breaches involved lost or stolen credentials. How can you keep pace?

Exabeam delivers SOC teams industry-leading analytics, patented anomaly detection, and Smart Timelines to help teams pinpoint the actions that lead to exploits.

Whether you need a SIEM replacement, a legacy SIEM modernization with XDR, Exabeam offers advanced, modular, and cloud-delivered TDIR.

Get a demo today!